其工作室马工业建筑在多伦多ybe small, but Iconoplast Designs has a large, impressive resume and very deep roots.

现在fourth-generation family business, it is one of the few plaster conservation businesses still existing.

Founded by third generation master plasterer and a plaster conservator Jean-Francois Furieri, its long list of projects includes the Pantages Theatre, One King West and the Royal Ontario Museum—all in Toronto—and several in other parts of Canada and the United States.

And that’s only a small sampling.

At one time it operated from a 5,000-square-foot facility and had two full-time crews for the production component of its business.

“More restoration is now being done insitu (on site) so we reduced our studio four years ago,” says Furieri in explaining why he relocated the business to its present location in the city’s east end.

As described by Furieri his trade is a very old one, although in the case of Iconoplast, one “infused with modern technologies and an intimate hands-on approach.”

Its five main areas of expertise include restoration, preservation, conservation, plaster repair, and custom fabrication. Examples of the latter can range from ceiling mouldings for new home builders to one-of-a kind pieces such as a wall frieze for fashion/fragrance designer Christian Dior’s Miami and New York stores, a copy of which is kept in the studio.

Whatever the project, however, the same principles of chemistry and geometry apply and the process starts with creating a drawing and then making a mould. Old photographs, drawings, sketches or drafts and even blueprints can provide insight.

“The objective is to preserve and conserve 100 per cent of the original plaster,” says Furieri, noting that’s not always possible and some sections have to be recreated.

Iconoplast Designs has been operating since the mid-1980s but its origins go back more than 100 years. Furieri’s grandfather, father, and uncle were sculptors in traditional plaster shops. In the early 1900s Furieri’s grandfather, Dominique, planned to emigrate from his native Italy to United States with the dream of landing a position with a movie production company.

“Most of the film sets at that time where made from plaster.”

Dominique only got as far as France where he got a position in the construction of a large hotel and where he settled and started a business. An heirloom from that era in the Toronto studio is a plaster cast of an address nameplate for a building on a street named after French author Victor Hugo. It would have been used as the prototype for a final version fabricated from either bronze or stone, says Furieri.

“But I don’t know too much about it or what city it was used in.”

Many of the business archives were lost when the family home in what-was-then French North Africa was destroyed by fire. Fortunately the cast was in a studio that was not part of the house and was part of the plaster family archives and family library which Furieri brought to Canada after founding Iconoplast in 1987.

Not unlike many young people whose fathers and grandfathers were in the same profession or trade before them, Furieri considered different career options including martial arts and was even short-listed to compete as a judo contestant in the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow.

Love and a sense of adventure changed those plans. His girlfriend and now wife, who he met in high school, wanted to return to Toronto where she was born.

In 1979 the couple immigrated to Canada and the following year he started working as a production manager for a plaster production company.

As he recalls it, the 1980s was “a period of transition,” because that was when the emphasis on building conservation and restoration in Toronto and throughout Canada was emerging. He still laments the fate of many of the city’s older houses where the old-style plaster was ripped out and replaced with drywall during renovations.

“Plaster walls provide better acoustics,” says Furieri.

Certainly in his case the 1980s was marked by series of seminal events. A year after starting Iconoplast he obtained his first “big break” when he was hired to construct 28 large capitals — the topmost members of columns — in Montreal’s new Cinema Egyptien which closed in 2001.

尽管这个项目没有产生多少publicity outside of Quebec, he subsequently received the award to restore the Pantages Theatre (now the Mirvish Theatre) in Toronto.

Capping the two-year-long undertaking, which included restoring the main lobby and nymphs on the main stage, was the 1989 opening of the Phantom of the Opera.

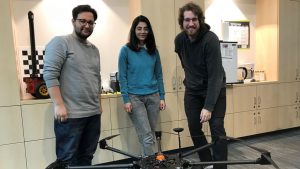

In the ensuing years a constant thread of projects followed including a recent one of national importance. Early in the new year Furieri, his daughter Magali and their assistant Jen Weber completed a five-month-long restoration in the House of Commons’ West Block — actually one component of an multi-phase overall rehabilitation of the block.

“We restored 12 capitals, the whole frieze on the stair lobby on the outside wall of the PMO (Prime Minister’s Office), and the whole cornice and friezes in the inside of the PMO, the wall ornamentations and the coats of arms.”

“They were in very bad shape. We had to retool and carve the ornaments to their original intended design by hand. It took hundreds of hours and a lot of patience,” says Magali.

The fourth generation of her family to embrace the craft, she resumed training and working with her father after graduating from a four-year historic restoration program at the School of Willowbank Arts in Niagara-on-the-Lake.

“My passion is plaster. I grew up with plaster,” she says.

Asked what has been their most challenging or satisfying assignment, Furieri replies: “It’s always the next one — it’s true. Once a project is done you don’t think of the problems.”

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed